What is working capital? Why does it matter to the sale of my business? If it’s so subjective, how can I ensure that I’m receiving a fair offer?

Read on to learn how TobinLeff’s industry expertise of M&A and working capital increased a sell-side client’s cash at close by more than 12%.

And in this latest article, get answers to these questions and explore:

- The importance of clearly defining “sufficient working capital” before reaching an LOI

- How “the Peg” can impact earnout

- How debt can be (mis)interpreted in working capital calculations

- How preparing your financials benefits your working capital

As always, feel free to contact Chuck, or any of the TobinLeff partners, with questions.

Click here for your complimentary copy: TL Working Capital White Paper

Working Capital – The Under Looked Critical Component of M&A Transactions

In most M&A transactions, during the pre-offer stage the focus is on the earnings of the company and the multiple applied to those earnings to determine value. When referring to earnings of MarComm agencies and service firms, the typical measurement is the free cash flow of the business in the form of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). EBITDA provides a clear picture and allows for an apples-to-apples comparison among multiple companies to help buyers evaluate just what they’ll be acquiring. Because the calculation of EBITDA is based on the underlying books and records (assuming they are accurate), this is an objective determination. As part of this process, sellers propose (subjective) adjustments for non-recurring items or costs that the buyer will not need to incur going forward. EBITDA net of these adjustments is referred to as Adjusted EBITDA or Normalized EBITDA.

The buyer then determines a multiple to apply to the Adjusted EBITDA. The determination of this multiple is subject to the buyer’s opinion of many things such as growth opportunities, synergies, recurring revenue, client concentration, size, and their acceptance of the adjustments, among others. Because of the multiple factors and the weighting that any buyer will apply to the factors, there is no objective way to determine the multiplier. This is where an advisor experienced in MarComm transactions can add much value both in weighing offers and in providing an expert voice to help sellers negotiate their best price.

After the parties have come to an agreement on the purchase price, both parties will sign a Letter of Intent (LOI) that outlines the agreed-upon financial terms. The LOI defines many elements of the planned transaction and almost always contains a critical and frequently sticky clause related to working capital. The Working Capital Clause generally reads to the effect of “the buyer will deliver sufficient(1) working capital to achieve the operating results”… and now the fun begins!

(1 Also commonly referred to as adequate working capital)

It surprises many sellers that they must leave any working capital in their business. While other owners think they need to leave only an equal amount of accounts receivable and accounts payable and a balance sheet of net $0, and the seller then will walk away with all the cash plus any excess receivables. The reality is usually much more complex.

Unfortunately, however, when no experienced advisors are involved representing the seller, the Working Capital Clause often is given only a cursory consideration by either or both parties before the LOI is signed. Then due diligence begins, and this turns out to have been a big mistake.

The determination of “sufficient working capital” is even more subjective than Adjusted EBITDA. There is no commonly accepted methodology to compute “sufficient working capital.” As a result, failing to put careful thought into the methodology and agreed upon definition before signing an LOI tends to lead to some very contentious discussions…and to the collapse of many deals.

Working capital, alone, is defined everywhere from accounting books to Investopedia as the difference between current assets and current liabilities. Current assets in this context include, at the very least, cash, accounts receivable, prepaid expenses, work in progress, and inventory. Among current liabilities are accounts payable, accrued expenses, and the current portion of long-term debt. If we could stop here and the calculation were simply working capital as defined by Investopedia, this would all be very easy. It’s the addition of the word “sufficient” that leads to sleepless nights.

Most deals are valued on a cash-free, debt-free basis. Cash-free, debt-free means that when a buyer purchases a company and its assets, the seller will pay off all debt and extract all excess cash prior to completion of the transaction. Excess cash is any cash held by the company being acquired that is more than the amount necessary to achieve sufficient working capital.

Because the deals are cash-free, debt-free to determine sufficient working capital for purposes of an M&A transaction, working capital is calculated excluding both cash and debt over a defined period of time to establish a pattern of working capital needs. Some buyers will look to the average of the trailing twelve months of working capital to determine this net working capital peg or simply “the Peg”, while others may use trailing 6 months, trailing four quarters, the high water mark of the last 6 or 12 months, or even forecasted future working capital requirements. Sophisticated buyers know that in the case of a growing company with positive working capital, using a shorter number of more recent periods (trailing 6 months versus trailing 12 months, for example) results in greater working capital being required to be delivered. These buyers will often select the period to be measured to try and make the expected impact most favorable to them. Fortunately, at TobinLeff, we know these tactics, as well, and are always alert for them when we are representing sellers.

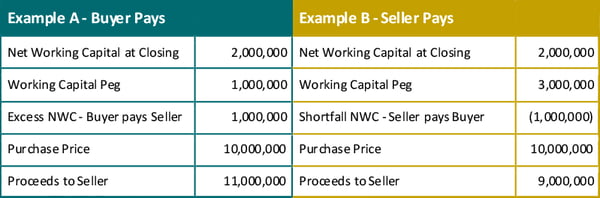

The establishment of the Peg is critical to the seller. For example, let’s assume the parties agree to 5X adjusted EBITDA of a company making $2 million, or $10 million. Next, let’s assume that working capital is $2 million at closing. Here is the impact of two different Pegs to the seller, one at $1 million and one at $3 million:

In Example A, the seller ends up with $2 million more in net proceeds than in Example B.

The Peg is compared to actual net working capital delivered at closing, and the difference in these numbers is a dollar-for-dollar adjustment to the purchase price. The reason for this is that buyers want to make certain that sellers don’t drain the working capital out of the business prior to closing by, for example, delaying paying vendors, depleting inventory, incentivizing customers to pay their accounts receivable balances early or perhaps providing an advance for future services, and then withdrawing the cash generated by these tactics. Without a working capital adjustment, the buyer would then end up with a company that has no receivables to be collected in the near future, no inventory, and past due payables.

Adding to the complications is the fact that a cash free, debt free transaction is not always the case. Some buyers will determine the average net working capital and then require an additional amount of cash on top of the average to mitigate the ebbs and flows of cash flow throughout the year. Sometimes this is a flat amount, and other times it is calculated as an average (hopefully using the same period as used for calculating the Peg) of operating expenses for one or two months or even as short a period as ten days. Working capital to be left behind by the seller then becomes the Peg plus this amount. This can often be an area for much negotiation. However, if a buyer selects the peg to be the high-water mark of working capital, they should not also request additional cash…but some will.

The elimination of debt from current liabilities during the working capital calculation is another common area of controversy. In the case of the current portion of long-term debt, there is no issue. But there are buyers who view other types of liabilities as being effectively debt and want them to be excluded from the working capital calculation and they want cash delivered by the seller in amount equal to these liabilities. Examples of these items include accruals for bonuses paid at year end and cash received from the seller’s clients for future work (retainers) and advances on media purchases. The logic for the inclusion of these items, which is valid, goes beyond the scope of this article, but suffice to say debt can be more broadly interpreted than simply notes payable and is another subjective area ripe for (mis)interpretation.

Another form of debt that is always excluded in working capital calculations is related party debt or obligations to and from owners. These amounts are generally shown as current assets or current liabilities on the seller’s books and buyers will exclude these from the calculations as they will not be delivered with the company upon sale.

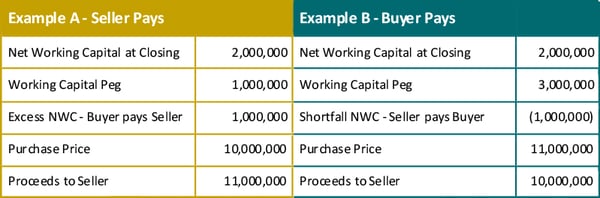

After the LOI has been signed, the power in the transaction shifts to the buyer. As a result, if “sufficient working capital” has not been clearly defined in the Letter of Intent, it can become an opportunity for a buyer to manipulate the methodology to disadvantage the seller. Moreover, if comparing two deals where “sufficient working capital” hasn’t been carefully defined, what appears to be a better offer may turn out to be just the opposite. For example, see the following case where the purchase price in Example B is $11 million compared to $10 million in Example A. Even with the higher purchase price in Example B, the net proceeds to the seller are lower than in Example A:

We have written articles in the past about the importance of getting your financial house in order before going to market. Working capital is another area that benefits from this exercise. Having detailed and accurate records will allow you to the control the dialogue, avoid surprises, and maximize the proceeds you receive for your life’s work. Specific items to be addressed and adjusted in your underlying books and records include:

- Properly accruing unpaid expenses and bonuses (e.g., accrue annual bonuses 1/12 per month, as opposed to recording 100% of the amount in December or recording these expenses on the cash basis which often times will not match the expense in the period to which it was owned).

- Adjusting A/R to expected realization (e.g., establishing a monthly reserve for bad debt as opposed to simply writing off bad debts when realized to be uncollectible).

- Properly recording prepaid expenses (e.g., if 6 months of rent is prepaid at the end of the year for tax purposes, an asset needs to appear on the books; if material, an item such as an annual software license should be expensed over 12 months).

- Properly recording deferred revenue (e.g., when receiving an advance payment from a client for future work, record a liability for that service to be performed rather than recognizing this as income upon receipt of the cash or the sending of the invoice; only include in deferred revenue amounts actually collected from clients or due and do not include advance billings).

Early on in this article we discussed Adjusted EBITDA. Since companies are valued on the Adjusted EBITDA basis, the last item to address regarding working capital is the removal of non-operating and non-recurring expenses from the working capital calculation so that the calculation is on a comparable basis with Adjusted EBITDA. This includes items such as removing amounts related to owner discretionary expenditures from accounts payable.

How does all of this play out in the real world? TobinLeff recently assisted a privately held company in preparing their net working capital calculation in response to what the buyer had submitted. The buyer and their Big 4 advisors out of Chicago created a Peg that, through protracted negotiations and utilizing the type of strategies we’ve been outlining in this White Paper, we ultimately were able to reduce enough to increase the seller’s cash at closing by more than 12%! In another situation, we recently worked with a client where the working capital Peg calculated by a nationally recognized regional firm had both mathematical and logical errors that we discovered. Identifying and raising these errors resulted in an extra $250,000 in our client’s pocket. Finally, we recently worked with a client after the acquisition and reviewed the net working capital at closing calculation, which is completed by the buyer after the closing, and identified adjustments that resulted in nearly $600,000 more to the seller than was calculated by the buyer in its initial net working capital at closing calculation.

The takeaway from all of this is that the definition and calculation of sufficient working capital is a complex and essential part of structuring any deal. When selecting a partner to help you sell your business, it is important that you consider not only their marketing skills, but their ability to represent you in all aspects of the deal.